Daniel Coit Gilman was born on July 6, 1831. He was the fifth of nine children born to Eliza Coit and William C. Gilman, a wealthy mill owner in Norwich, CT. William Gilman also served as mayor of the city from 1838-1840. At the age of twenty, Daniel graduated from Yale College in 1852.

Daniel Coit Gilman was born on July 6, 1831. He was the fifth of nine children born to Eliza Coit and William C. Gilman, a wealthy mill owner in Norwich, CT. William Gilman also served as mayor of the city from 1838-1840. At the age of twenty, Daniel graduated from Yale College in 1852.

Shortly following his graduation, he procured a position as attaché to Connecticut state governor Thomas Seymour who had been appointed as Minister to Russia by President Franklin Pierce. Gilman accompanied Seymour on diplomatic missions not only to St. Petersburg, Russia but to capitols throughout the European continent. It was during these visits to Europe that he became acquainted with the institutions of higher learning that existed in England, France, and Germany. The knowledge he gleaned about European schools that excelled in technical and scientific training became the catalyst for Gilman’s lifelong mission to improve higher education in the United States.

When his tenure as a diplomatic attaché was completed he was appointed to an assistant librarianship at Yale, and later in the role as a full librarian. In 1863 Gilman was given the position of professor of physical geography in the Sheffield Scientific School, an affiliate institution of Yale College.

It was during the decade between 1860 and 1870 that certain leaders within the American educational hierarchy began to emphasize the importance of technical and industrial schools. This phenomenon was spurred on with the passage of the Morrill Act in 1862 which provided federal grants to all of the states to establish land grant colleges for “agriculture and the mechanical arts”. In 1871 Gilman was appointed by the federal government to investigate what the potential barriers might be to successfully implementing the Morrill Act. His investigation revealed that the key obstacle to expanding higher education was the lack of qualified professors to teach students at these proposed institutions for scientific education. Even elite colleges like Yale and Harvard had relatively weak science curriculums and the majority of both school’s faculties were comprised primarily of prominent members of the clergy.

In 1871 Gilman became the president of the University of California but ultimately he left the university after just two years due to the stiff resistance to the educational reforms he had proposed. However, in 1875 a near-perfect opportunity presented itself. Johns Hopkins, a wealthy merchant bequeathed the largest financial gift for the development of higher education in American history. The vision entailed the creation of a brand new type of university that would modernize the educational processes of higher education. Daniel Gilman was the unanimous choice to be the new university’s president. Just after accepting his new position he summed up the goals of the new university: “What are we aiming at? The encouragement of research and advancement of individual scholars, who by their experience will advance the sciences they pursue.”

During his twenty-five-year tenure (1876-1901) at the helm of Johns Hopkins University, Gilman assembled a distinguished faculty of many of the top educators in their respective fields and displayed his genius as an organizer and administrator. He masterminded the creation of both Johns Hopkins Medical School and Johns Hopkins Hospital.

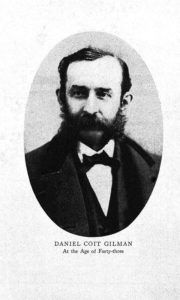

To view images of Daniel Coit Gilman, the most influential innovator of post-graduate education in American history visit the Otis Library’s Flickr page.