In 1796, John and Sam Trumbull established the Norwich Circulating Library at John Trumbull’s printing office for the local newspaper, the Norwich Packet. The library provided the public access for a basic fee to a collection of over 300 volumes on varied subjects, including History, Biography, Geography, as well as novels and poetry. Circulating libraries for the public dissemination of books had become popular in England following the Enlightenment era during the 17th and 18th centuries in Europe. The invention and widespread printing of books, journals, and pamphlets had already facilitated increased literacy among the general public. American colonies, particularly in the Northeast, were steeped in book culture, with literacy rates among colonists reaching an impressive 90 percent by the middle of the 19th century.

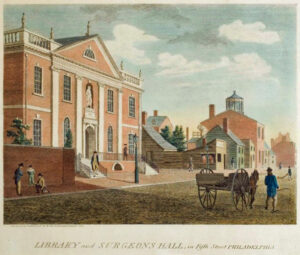

More than half a century earlier, a new and singularly American model for public libraries evolved, known as the subscription library or the social library, as it was sometimes called. The model required members, or subscribers, to pay annual dues, which were collectively used to purchase books for the general library collection. One of the earliest and culturally significant subscription libraries was the Library Company of Philadelphia, created in 1731 by Benjamin Franklin and his associates in the Junto social club. Subscribers to this company, for instance, paid 10 shillings yearly. The core mission of the Library Company was explicitly educational and philosophical: to elevate the level of intellectual discourse among middle-class merchants and tradesmen by exposing them to a collection of papers and books that reflected the principles of the Enlightenment in science and philosophy. Approximately 50social libraries modeled after the Library Company were established in New England between 1733 and 1780,

The Library Company of Philadelphia also served as a meeting place for some of the members of the First Continental Congress, with 10 of the library’s members ultimately becoming signers of the Declaration of Independence. It also served as the incipient repository for the earliest version of what eventually became the nation’s Library of Congress.

Subscription libraries similar to the Library Company focused on philosophy and civic improvement. They played a pivotal role in the dissemination of revolutionary concepts, such as John Locke’s view of the “pursuit of life, liberty, and property,” and Montesquieu’s theory advocating for the separation of powers across all three branches of government (executive, legislative, and judicial). Thomas Paine’s bestselling pamphlet Common Sense was published in 1776. It was a highly influential piece of literature that radically influenced the political ideals of colonists and became more readily available through subscription libraries throughout the colonies. Ultimately, subscription libraries were vital infrastructure for the widespread dissemination of knowledge and the revolutionary ideas that shaped the American political landscape.

Though subscription libraries played an essential role in shaping the American colonists’ ideas about representative democracy, it must be noted that these libraries, like so many other cultural venues were restricted to well-heeled white men. Women were unable to access public libraries until 1830, and Black Americans were often barred from public libraries during the 18th century and most of the Jim Crow era in some regions of the United States.