During the colonial period in America, persons suffering with commonplace maladies often sought out the local apothecary for medicinal remedies. At this time in American history there was not a clear delineation of roles between the person that prescribed the most expedient remedy and the person who prepared the medicine. In most cases it was the same person. Ingredients for these remedies were derived from medicinal plants found in North America and the Caribbean region. The knowledge of the natural healing properties of these plants having been gleaned from the indigenous inhabitants in these locales whom ironically the early English settlers had displaced. The local apothecary was also where bottles of patented medicine often of a dubious nature from the United Kingdom might be purchased.

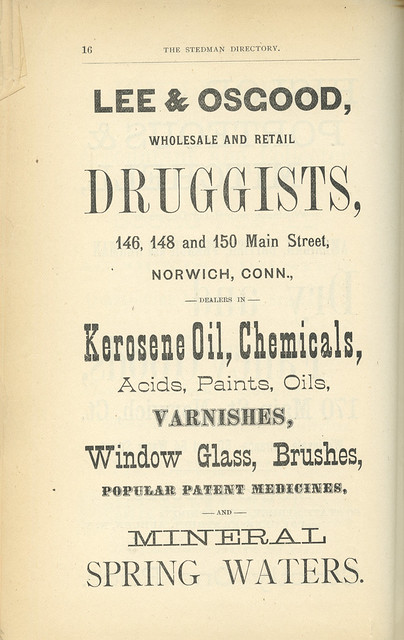

During the late 17th century England, a medicine could receive a royal stamp of approval or patent by publicly disclosing the chemical makeup of its product. In fact, few purveyors of these medicinal products divulged the list of the actual ingredients. Rather, they ascribed hyperbolic claims for the curative power of their product’s ability to heal a laundry list of maladies. As in the United Kingdom, unregulated patent medicines in the United States enjoyed a lucrative symbiotic relationship with the burgeoning newspaper advertising industry. In addition to the persuasive power of newspaper advertisements, some American manufacturers of patent medicines exploited the heritage of Native Americans employing traveling “medicine shows” claiming their product was based on ancient and secret herbal remedies of an indigenous tribe. The Kickapoo Indian Medicine Company based in New Haven, CT was assuredly the most egregious perpetrator of this marketing strategy.

While many patent medicines contained components that were ineffectual and clearly not curative, some of these elixirs contained substances such as laudanum and cocaine that were not yet understood to be addictive. Laudanum, a tincture of opium became an accepted and popular supposed curative for all types of maladies. A popular over-the-counter product, laudanum was used for treating the common cold and its symptoms, providing general pain relief, treating meningitis, a corrective for host of women’s health issues, a surgical anesthetic and even a soothing remedy for teething infants. During the Civil War both laudanum and morphine were routinely used by the medical staff to treat wounded soldiers, unknowingly triggering the nation’s original opioid crisis. Thousands of soldiers returned from the war as opium addicts suffering from a physical illness that became known as “opium slavery”.

By the late nineteenth century the realization that opiate addiction was a substantial societal ill that required federal regulation was accepted by the American public. In 1906 Congress passed the Pure Food and Drug Act which required manufacturers of all patent medicines to list their ingredients prominently on their products. Faced with this public scrutiny, many manufacturers were forced to remove all harmful and addictive substances from their patent medicines and in some cases, withdraw their products from the market.

To view images of some of the local Norwich pharmacies that existed during the nineteenth century and newspaper advertisements for popular patent medicines of that era visit the historical photographs link on Otis Library website.